Self-citation, cumulative advantage, and gender inequality in science

Author: Pierre Azoulay

Author: Freda B. Lynn

Abstract: In science, self-citation is often interpreted as an act of self-promotion that (artificially) boosts the visibility of one’s prior work in the short term, which could then inflate professional authority in the long term. Recently, in light of research on the gender gap in self-promotion, two large-scale studies of publications examine if women self-cite less than men. But they arrive at conflicting conclusions; one concludes yes whereas the other, no. We join the debate with an original study of 36 cohorts of life scientists (1970–2005) followed through 2015 (or death or retirement). We track not only the rate of self-citation per unit of past productivity but also the likelihood of self-citing intellectually distant material and the rate of return on self-citations with respect to a host of major career outcomes, including grants, future citations, and job changes. With comprehensive, longitudinal data, we find no evidence whatsoever of a gender gap in self-citation practices or returns. Men may very well be more aggressive self-promoters than women, but this dynamic does not manifest in our sample with respect to self-citation practices. Implications of our null findings are discussed, particularly with respect to gender inequality in scientific careers more broadly.

Date: 2020

Volume: 7

Pages: 152–186

Publication: Sociological Science

Date Added: 11/9/2021, 11:41:09 AM

Reading Notes:

Objective: To measure the existence of a gender gap in self-citations and the rate of return in self-citation by gender

Importance: Two recent studies on this topic came to conflicting conclusions. This study is aimed at being more comprehensive, with 36 cohorts of life scientists

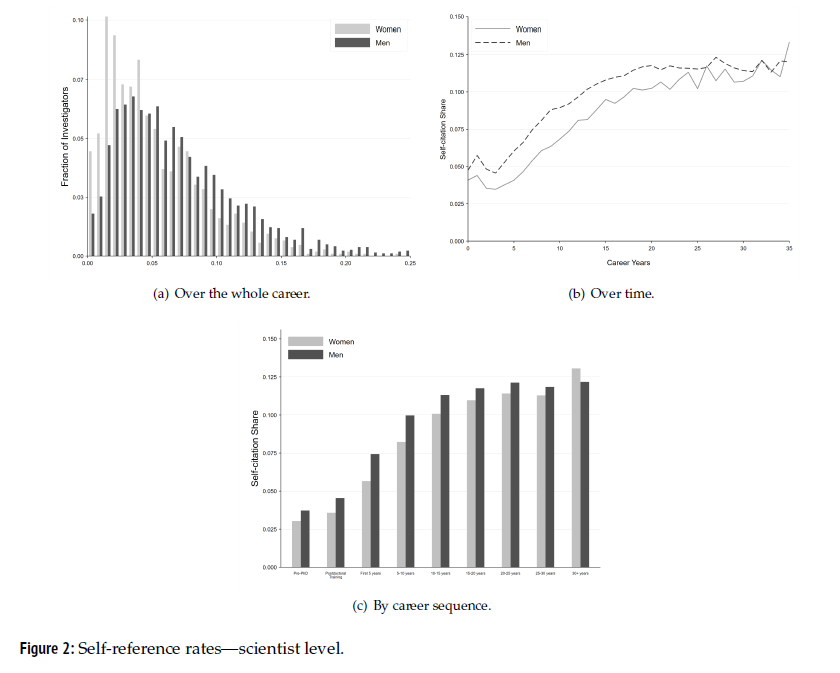

Background: ~9% of all citations are self-citations, with higher percentages in some fields (physical sciences) than others (humanities). Multi-authored papers have more self-citations.

King et al (2017) find self-citation is 70% higher for men than women, using papers in JSTOR, but they do not control for # of papers or career age.

Mishra et al (2018) control for # of papers and find no self-citation gender gap in PubMed papers

Data & Key Variables:

Longitudinal study of the winners of postdoctoral fellowships - total of 3,667 life scientists, "star" graduate students

Publications, references, citations, NIH grants, & patents

Exits from science, exits from academia, exits from "stable" to "marginal" position within academia

Methodology:

Prob(self-cite)=B0+B1*Woman+B2*Relatedness Indcator+B3*Total Pubs & Pub Characteristics+B4*"Predetermined Covariates"

Outcome=B0+B1*Woman+B2*Total Pubs+B3*Total Pubs*Woman+B4 Frac Self-Cite+B5*Frac Self-Cite*Women

Hazard model for exits

Results: There is a gender gap in publications, which accounts for the disaggregate discrepancy in self-citation.

If stock of previous publications to potentially self-cite from is controlled for, the gender gap in self-citation disappears

Self-citation does not appear to be associated with positive career outcomes. It is neutral or even negative (controlling for # of publications)

Comments: External validity? Looking at biology students who were fellowship winners (top of their programs)

Key Table/Figure: